This article appears in the February 1995 edition of the Catholic Medical Quarterly

Return to February 1995 CMQ

Neuropathological findingss

in cases of

Persistent Vegetative State.

The medical condition of Anthony Bland and the legal decisions relating to the discontinuation of his tube feeding received prominent media attention. This journal has already covered some aspects of that debate, including a review of the persistent vegetative state (PVS) by a Guild member expert in its treatment and rehabilitation. Sadly many used the case to try and advance the cause of euthanasia. To try and justify the decisions being made some individuals, including a doctor, made statements to the media that Tony Bland's brain was now liquified.

The Guild has received permission from Tony Bland's parents to publish details of the pathological findings of Tony's brain. We are also grateful to the coroner and pathologists involved for releasing their reports to us. This short paper will describe the findings in Tony Bland's brain and will make comparisons to that of Karen Quinlan - an earlier case of PVS from the America which received widespread publicity during passage of its legal proceedings.

Tony Bland, at the age of 18, suffered an episode of cerebral anoxia subsequent to the crush injuries he received during the Hillsborough disaster on 15th April 1989. He was subsequently diagnosed as suffering from PVS. On the 4th February 1993, the Law Lords upheld the decision of lower courts that it was legal for the doctors to withdraw the nutrition and hydration on which he was dependant. He died at 2115hrs on 3rd March 1993. The post mortem showed a degree of cachexia with a body weight of 36 kgs. There were flexion contractures of the arms, right wrist and fingers as well as flexion and adduction of the left thigh and bilateral plantar flexion of both feet, more marked on the right. Examination of internal organs showed bronchopneumonia, pyelitis, cystitis and a periprostatic fistula with loculated pus.

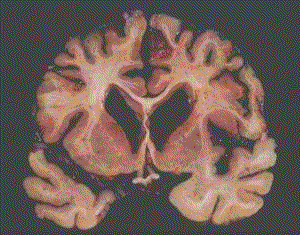

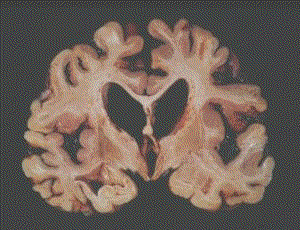

The brain weighed 1007 gms (normal about 1300gms). The gyri were narrowed, particularly over the lateral and occipital poles. These findings indicate a significant degree of cerebral atrophy. For comparison, the brains of patients suffering from severe dementia are often less than 1000gms in weight. Examination of the cut surface of the brain (Figs 1 and 2) showed widespread loss of the cortical grey matter, which in places was 1-2 mms wide (normal 2-4 mms). There was also bilateral dilation of the ventricles, further confirming the widespread cerebral atrophy.

At the age of 21, Karen Quinlan suffered a cardiorespiratory arrest following an accidental ingestion of alcohol and prescribed sedatives. Although she was pulseless, cyanosed and had fixed dilated pupils when found, she was successfully resuscitated. In the initial stages she was being ventilated and the family sought court approval to discontinue artificial ventilation, classed as extra-ordinary treatment. The legal proceedings received much media attention at that time in 1976. However when ventilation was discontinued she continued to breathe spontaneously and lived for a further 9 years. She was also diagnosed as suffering from PVS.

Overall Karen's brain showed severe atrophy (weight 835 gms). She was also severely cachectic with a body weight of only 27 kgs. Although there was cortical damage especially in the parasaggital parietal and occipital cortex, there were areas where the cerebral cortex was well preserved and there was sparing of the brain stem, basal forebrain and hypothalamus. The pathologist, in that case, noted that the most severe damage was in the thalamus. Comparison of the published photographs of Karen' brain2 and Tony Bland's brain (Fig 2) show that in the latter the thalamus is relatively well preserved, although there was microscopic evidence of thalamic neuronal loss.

We have therefore two cases with similar presentation (anoxic brain damage) and with similar clinical features (persistent vegetative state). Although pathological examination in both cases confirmed severe anoxic damage, there are significant differences not only in the degree of damage but also in the main site of damage. Although our understanding of cerebral function is quite extensive, with mapping at the functional level of the motor and sensory cortex and a fairly sophisticated understanding of some of the processing that occurs in both the retina and visual cortex, there are also vast areas of the brain (the so called silent areas) where we have very little understanding of their function. The experience of neurosurgeons regularly reveals how, in some cases of trauma and tumours, large areas of the brain can be removed and yet there is good post operative functional recovery. Conversely slight damage to other small areas of the brain can have devastating clinical effects.

The authors of the article describing Karen Quinlan's pathological findings draw attention to the limitations of our understanding of the neuroanatomical basis for human consciousness. At one time consciousness was though to reside in the cortex, then came our understanding of the limbic system and the role of the brain stem reticular formation in cerebral arousal. The findings in Karen Quinlan's brain suggested that the thalamus played a more crucial role in consciousness and awareness than was previously thought.

The variability of damage to different parts of the brain described in case reports of patients diagnosed as suffering from PVS, highlights the limitations of our understanding of human brain function. On a practical basis this should make us vigilant in how we talk when within earshot of unconscious patients. We should also be cautious that we do not equate lack of response to external stimuli as evidence that there is no awareness. Do we really have the scientific certainty to be able to dogmatically state that any particular patient has no awareness and in unable to experience discomfort? I accept that there may be no external manifestation of awareness of discomfort, but I doubt whether the objective certainty exists to support the statements made by some, that there can be no distress. That uncertainty in this area exists was certainly conveyed to the Law Lords, otherwise why should Lord Goff of Chieveley say in his judgement "Furthermore, we are told that the outward symptoms of dying in such a way, which might otherwise cause distress to the nurses who care for him or to members of his family who visit him, can be suppressed by means of sedatives."

Our lack of knowledge should not, however, deter us from making decisions about the futility or wisdom of various medical interventions. We can only make judgements based on our current state of knowledge. I have no difficulty accepting that a diagnosis of brain stem death equates with a statement that there is no likelihood of recovery and so all further treatment is futile. I believe that our approach to patients should be governed - unless based on sound scientific knowledge such as is available in aspects of anaesthesia - by the premise that the patient might have some awareness. If we adopt this view we shall be confident that we will never do anything that causes unnecessary suffering. We hold that the dignity of our patients is due to their being human, and however abnormal the pathological state of their various organs, their dignity as human beings can never be lost.

Dr Michael Jarmulowicz. FRCPath, MBBS, BSc.

Consultant Histopathologist.

References: