Catholic Medical Quarterly Volume 69(3) August 2019

Faith in Medicine

A Moral Compass to Guide Me

Dr Donna Rompey

Abstract

This narrative is a true account of a 38 year old woman’s efforts to

cope with the ethical questions that crop up in her mind while

pregnant with her second child. As she hails from a medical

background, she can fully comprehend the advice and choices offered to

her by her obstetrician. She is also aware of the consequences of

various screening and diagnostic tests for foetal anomalies. At the

same time, the deep religious convictions that she shares with her

husband are oft in conflict with current medical knowledge and

practice. An analysis of the medical facts of the case and adherence

to values of their inherent Christian faith enable the couple to

decide the next course of action, in the best interests of the mother

and child.

Key Words: ethical, screening tests, foetal anomalies, religious,

Christian faith

“I call heaven and earth as witnesses today against you, that I have

set before you life and death, blessing and cursing; therefore choose

life that both you and your descendants may live;”

Deuteronomy 30:19

[1]

My story unfolds in the hill station of Shillong in northeast India. As a 38 year old woman in my second gravida, I was wondering whether to follow my obstetrician’s advice of going for a triple test in the 18th week of my pregnancy. I was happily married and had a 7 year old daughter. I had recently undergone an anomaly scan which revealed no obvious foetal malformations on ultrasonogram. I was thinking that if the results of the triple test turned out to be positive, I would probably have to go ahead with an invasive procedure called amniocentesis to find out if the foetus has a chromosomal abnormality. These screening and diagnostic procedures would have to be performed before the 20th week of gestation, so that I would have a choice of either continuing the pregnancy or terminating it on eugenic grounds, as per Indian law.

Medical facts

The triple test is employed to screen for foetal anomalies during the second trimester of pregnancy in women over 35 years of age.[2] It measures levels of markers a-fetoprotein (AFP), unconjugated oestriol and human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG) in maternal serum. There is a 5% chance of a false positive result, creating unnecessary alarm to the parents.[3] It is also not an end in itself, but rather the beginning of a series of procedures to confirm or rule out the risk of having a disabled child. If the triple test results fall in the high risk category, the patient is usually advised diagnostic amniocentesis or chorionic villus biopsy to study the foetal karyotype. Amniocentesis involves extraction of fluid from the amniotic cavity through the abdominal route under ultrasonic guidance. It is associated with a 0.5-1% risk of foetal loss.[4] At the same time, because of the 5% false positive nature of the screening test, there are possibilities of losing a perfectly normal baby during this invasive procedure. The risk of foetal aneuploidy, primarily trisomies, increases with maternal age.[5,6] The additional age-related risk of non-chromosomal malformations is approximately 1% in women 35 years of age or older.[7]

This hard evidence justifies and supports my obstetrician’s well-founded advice for me to undergo the screening test.

Legal aspects

The Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act was passed

in India in the year 1971,[8] with a view to curbing unsafe abortion

practices performed in unsanitary conditions by unskilled personnel. It

legalises abortion by a qualified doctor at a recognised centre on

therapeutic, eugenic, humanitarian and social grounds. However, medical

and surgical procedures cannot be performed after the 20th week of

gestation, which is the legal cut-off for termination. A woman can obtain

an abortion on her own consent if she is a mentally sound adult over 18

years of age.

As far as my case is concerned, if the foetal karyotype

indicates a chromosomal abnormality such as Trisomy 21, which could result

in the birth of a seriously disabled child, it would not be illegal for me

to terminate the pregnancy on eugenic grounds.

Ethical considerations

I examined the morality of my possible choices in the

light of the core principles of biomedical ethics described by Beauchamp

and Childress.[9] Firstly, I had the right to determine what would be done

to my own body (principle of autonomy). I could make an informed decision

after understanding the risks, benefits and consequences of the proposed

investigation. Secondly, would the triple test be in my best interests?

(principle of beneficence). Thirdly, would the results of the test harm me

psychologically? How would the subsequent invasive procedure affect my

baby? (principle of non-maleficence). Fourthly, the triple test is neither

free of cost nor readily available in local hospitals and laboratories. A

pregnant woman who opts for it has to give her blood sample at a specified

collection centre in Shillong, from where it is sent to another location

for testing. These may not have been issues for me personally, but surely

would have influenced the choices of a poor patient hailing from a remote

area of northeast India (principle of distributive justice). The most

important ethical consideration is the sanctity of life which must be

respected at all costs. This is one of the basic tenets of medical ethics

enshrined in the Hippocratic Oath.[10] Its importance in my situation

applies to two precious lives – my life and that of the child I am

carrying. Often, conflicts may arise between the individual autonomy of

the woman and the rights of the child in the womb. In a sense, promoting

the mother’s wellbeing may be at the cost of harming her child.

These

thoughts only served to deepen the moral dilemma I was facing.

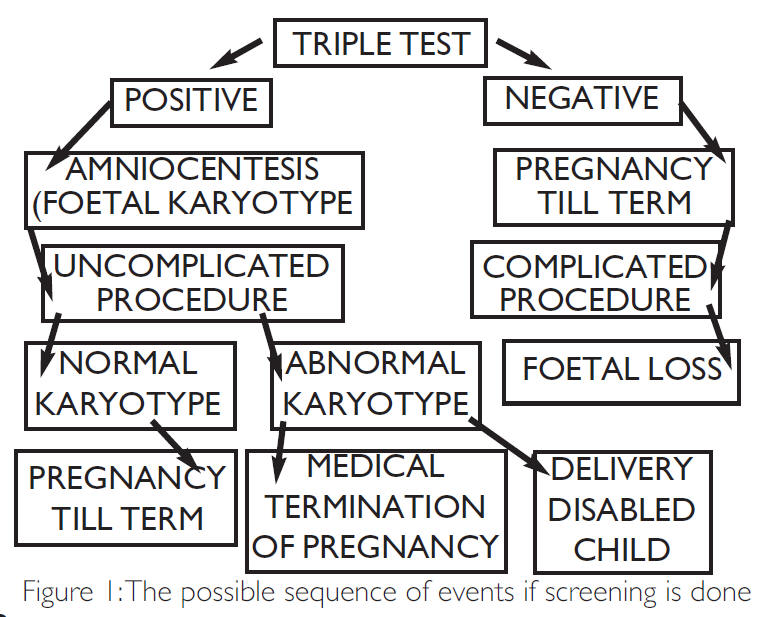

The dilemma – To screen or not to screen

I pondered on the fact that screening was just the initial step. If the odds were against me, I would have to go through a sequence of events whose end result may not be to my liking or approval (Refer to Figure 1). Should I just do it anyway on the presumption that no untoward event would occur; that the screen would just be a routine procedure with normal results? Or should I choose not to go ahead with it, hoping against hope that pregnancy would continue to term? At that point of time, I was mentally prepared to accept the possibility and consequences of having a disabled child by virtue of my late maternal age. The silver lining behind the clouds was the chance of having a completely normal child, free from disabilities, because even the best screening and diagnostic tests have their shortcomings. Medical procedures are not always decisive or foolproof. Moreover, I would rather not know what the future holds but trust God who holds the future.

“Your eyes

saw my substance, being yet unformed.

And in Your book they all were

written,

The days fashioned for me,

When as yet there were none of

them.”

Psalm 139:16 [1]

A Moral Compass

I spent some time mulling over my situation but realised I would have to decide whether to take the test or not sooner rather than later. I discussed the matter intensively with my husband, my closest confidante, as I found solace in sharing my problem and getting it off my chest. It also helped us to re-focus on what was really important to us as a married couple. We then took a joint decision in the best interests of both mother and child based on the following considerations:-

- A false positive triple test result would make us needlessly anxious with the erroneous anticipation of having an abnormal child.

- Screening was not the end, but rather the beginning of a chain of events whose final result might have been in conflict with our deepest convictions.

- Abnormal tests could have ended up in abortion, which we were not considering, because of our religious beliefs.

- Amniocentesis, the invasive diagnostic procedure recommended after an abnormal triple test, is associated with a 0.5-1% chance of foetal loss.

- My conscience, that deep inner voice inside me, told me that I must continue my pregnancy against all odds.

“Trust in the Lord with

all your heart,

And lean not on your own understanding;

In all your

ways acknowledge Him,

And He shall direct your paths.”

Proverbs 3:5,6 [1]

- There were possibilities that the baby may not be deformed at all; it was too soon to give up on him/her.

- Even if I gave birth to a disabled child, my husband and I would accept him/her just as he/she is because he/she is a gift from God.

Finally, my moral compass guided me to exercise my autonomy and make an informed choice to opt out of the triple test.

“Your word is a lamp to my feet and a light to my

path.”

Psalm 119:105 [1]

Footnotes

Four years later, we have no regrets regarding our decision, for our little baby is today an active andintelligent little girl, attends school and has a great sense of humour.

Figure 1

References

- The Holy Bible. New King James Version. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson Inc.; 1982

- Reynolds T. The triple test as a screening technique for Down syndrome: reliability and relevance. Int J Womens Health 2010; 2: 83-88. doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S8548 (accessed 4 Mar 2016).

- Baxi A, Kaushal M. Awareness and Acceptability in Indian Women of Triple Test Screening for Down’s Syndrome. The Internet Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 2007; 9(2). http://ispub.com/IJGO/9/2/8714 (accessed 11 May 2016).

- Oats J, Abraham S, eds. Antenatal care. In: Llewellyn-Jones. Fundamentals of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 9th ed. Edinburgh: Mosby Elsevier 2010:40-42.

- Johnson JA, Tough S. Delayed childbearing. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2012 Jan;34(1):80-93.

- Congenital anomalies. WHO factsheet. Updated April 2015. www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs370/en/ (accessed 2 May 2016)

- Hollier LM1, Leveno KJ, Kelly MA, McIntire DD, Cunningham FG. Maternal age and malformations in singleton births. Obstet Gynaecol 2000 Nov;96(5, Part 1):701-6.

- The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act No. 34 of 1971. Published in the Gazette of India, Ministry of Law and Justice, on 10 Aug 1971.

- Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 5th ed. New York: Oxford University Press 2001.

- Jones DA. The Hippocratic Oath II: The declaration of Geneva and other modern adaptations of the classical doctor’s oath. Catholic Medical Quaterly 2006 Feb. www.cmq.org.uk/CMQ/2006/ Contents-Feb-2006.html (accessed 24 May 2016.)

Dr Donna Ropmay is Associate Professor,

Department of Forensic

Medicine,

North Eastern Indira Gandhi Regional Institute of Health and

Medical Sciences,

Shillong –Meghalaya, India.

Conflict of interest:

None to declare

Source of funding: Nil

Disclaimer: The views

expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the

official position of the institution.