Catholic Medical Quarterly Volume 68(1) February 2018

The Patient’s Passion

by Fr Gary Dickson

![]() Suffering

is a sad reality that we meet every day in our professional practice, and

often enough in our personal lives too. Making sense of suffering is

necessary if it is not to demoralise us, and the first thing to say is

that suffering is not a punishment for our personal sins as some claimed

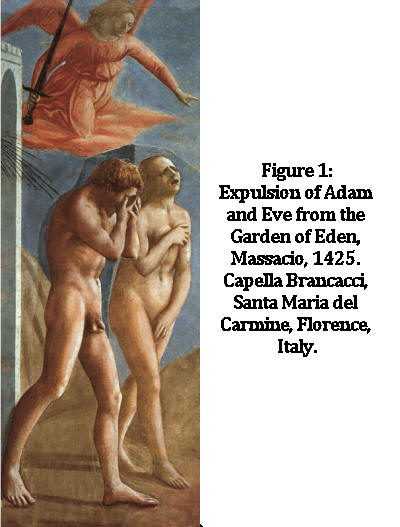

at the height of the AIDS crisis. Rather, suffering and death are the

result of the Original Sin, by which man cut himself off from God Who

alone is life, happiness and peace, thereby gaining only the opposites:

sorrow, suffering and death. Just as some personal sins can have negative

effects upon health, such as gluttony, sloth and promiscuity, so the

effects of the Original Sin - the loss of life, happiness and peace - are

a consequence, not a punishment. Negative consequences of sin are of

Suffering

is a sad reality that we meet every day in our professional practice, and

often enough in our personal lives too. Making sense of suffering is

necessary if it is not to demoralise us, and the first thing to say is

that suffering is not a punishment for our personal sins as some claimed

at the height of the AIDS crisis. Rather, suffering and death are the

result of the Original Sin, by which man cut himself off from God Who

alone is life, happiness and peace, thereby gaining only the opposites:

sorrow, suffering and death. Just as some personal sins can have negative

effects upon health, such as gluttony, sloth and promiscuity, so the

effects of the Original Sin - the loss of life, happiness and peace - are

a consequence, not a punishment. Negative consequences of sin are of

God’s

permissive will rather than His positive will, by which we mean He permits

us to suffer the effects of our choices but does not purposely inflict

that suffering on us as a punishment. To understand suffering and

death in this abstract way does not console the suffering person, nor does

it comfort their loved ones who stand with them in their suffering. Nor

does it keep the health care professional from emotional import when faced

with the task of alleviating that suffering. A meaning to suffering must

be held that goes beyond such abstract knowledge. For those of us who are

Christians we must have a more positive picture; we must speak of “the

Mystery of Suffering” rather than “the problem of suffering”, for the

suffering of Christ purchased our salvation: “on Him lies a punishment

that brings us peace, and by His wounds, we are healed” (Is.53v5), and our

participation in that suffering brings us to eternal glory; we are

“co-heirs with Christ if we share in His sufferings in order to share also

in His glory” (Rom.8v17). It is then, in the context of Christ’s Passion

and Death that we must see human suffering.

God’s

permissive will rather than His positive will, by which we mean He permits

us to suffer the effects of our choices but does not purposely inflict

that suffering on us as a punishment. To understand suffering and

death in this abstract way does not console the suffering person, nor does

it comfort their loved ones who stand with them in their suffering. Nor

does it keep the health care professional from emotional import when faced

with the task of alleviating that suffering. A meaning to suffering must

be held that goes beyond such abstract knowledge. For those of us who are

Christians we must have a more positive picture; we must speak of “the

Mystery of Suffering” rather than “the problem of suffering”, for the

suffering of Christ purchased our salvation: “on Him lies a punishment

that brings us peace, and by His wounds, we are healed” (Is.53v5), and our

participation in that suffering brings us to eternal glory; we are

“co-heirs with Christ if we share in His sufferings in order to share also

in His glory” (Rom.8v17). It is then, in the context of Christ’s Passion

and Death that we must see human suffering.

We must speak of “the Mystery of Suffering” rather than ‘the Problem of Suffering”, for the suffering of Christ purchased our salvation…

While Saint Peter takes up Isaiah 53 to remind us that, “By His wounds, we are healed” (1 Peter 2:24), Saint Paul informs us that such suffering has the positive value of being redemptive: “I make up in my own body that which is lacking in the sufferings of Christ” (Col1:24). Of course nothing intrinsic lacks in the suffering of Christ; all that it lacks is our participation in it: we share in the Easter Sunday experience only after having undergone the Good Friday experience, and we share in the Good Friday experience by our prayer, our sacrifice and our suffering. These do not enable us to win, deserve or purchase salvation; they are but the way in which we take the Good Friday experience to ourselves that we may also experience Easter Sunday. But there are further values to partaking in the sufferings of Christ.

A life of prayer in this is essential. By praying for ourselves to embody the humility, knowledge, skill and compassion of God for those who suffer…we bring God into the otherwise dark situation of suffering and death…

First, it enables us to become co-redeemers with Christ. Christ of course is not ‘co-anything’: He alone is Redeemer: “there is but one mediator between God and man, the man Christ Jesus, who gave Himself as a ransom for all” (1.Tim.2v5) but He allows us to cooperate with Him in His great work of Redemption: to “fill up…whatever is lacking in the sufferings of Christ” (Col.1v24). Second, suffering reminds us that man is not in charge of his own destiny and opens us up to a humble, conscious dependence upon God and His grace. It reminds us that we are not God; that no matter how high the pedestal the general public gives healthcare workers to stand upon we are, in the final analysis, going to fail: all our patients will one day die. All we can do is ask God for the grace to work humbly with His wisdom, His compassion and His skill.

A life of prayer in this is essential. By praying for ourselves to embody the humility, knowledge, skill and compassion of God for those who suffer, and by praying that our patients will benefit from the knowledge, skill, and compassion of health workers, we bring God into the otherwise dark situation of suffering and death, and the greatest prayer we can offer is Holy Mass.

We should take every opportunity to attend Mass regularly and offer the Holy Sacrifice for those who suffer so as to unite them to Christ on the Cross who even now, pleads His sacrifice before the Father on behalf of the world: “Christ … entered into heaven itself to appear now before God on our behalf” (Heb.9v24); “Christ Jesus, who died, and more than that was raised to life, is at the right hand of God, interceding for us” (Rom.8v34). He is still the Lamb slain in sacrifice (Rev.5v6). We may not be able to attend every day, but we can offer our daily prayers in union with the Masses going on at that moment, and give them a value beyond the worth that comes from praying alone. As we stand at the foot of the cross (the patient’s bed or chair) we should also call upon the Mother of the Afflicted who stood by the Cross of her Son. Her very presence brought courage and strength to her Son, and we can ask her to obtain from Him for our patients that same courage and strength.

An interior struggle begins; their experience of the Garden of Gethsemane

Consider for a moment the reality of The Holy Eucharist: it encompasses Christ’s farewell Supper with His Apostles; His Agony in Gethsemane; His Carrying of the Cross; His Crucifixion, Death and Resurrection. Each of these parallels an aspect of life in those we care for. Those given a diagnosis of terminal illness enter the Garden of Gethsemane where the prospect of suffering and death stands squarely before them. Every new limitation they encounter; every loss in their ability to perform the activities of living is a loss which brings with it a sense of grief, and a reminder that they are on ‘the downward slope to death’. An interior struggle begins; their experience of the Garden of Gethsemane. From the dread of what is to come arises the plea to have the chalice of suffering taken from them, either by intervention of the medical staff or the direct intervention of God. Kubler-Ross identified this stage in her book ‘On Death and Dying’ as the Bargaining Stage; either a bargaining with the physicians: “If I do A, B or C will you be able to cure me?” or with God: “I promise never to do A, B or C again if you cure me”.

For those of us who are in good health the prospect of death is a reality we rarely contemplate; for the sick and suffering that prospect is a daily companion. Many, if not most, seem to give great example of how death is faced with dignity and courage; rejoicing in what they can still do and the pleasures they can still experience rather than the losses they undergo, thus the many funeral eulogies which say “s/he fought bravely and cheerfully right to the end”. In this on-going struggle they become another Simon of Cyrene: they move from the Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane to carrying the cross with Christ.

As health care professionals, we are called and dedicated to caring, not killing.

The period when people approach the end of their lives is often clearly their participation in the Crucifixion, and here we should be doing as the soldiers did with the soaked sponge: offering whatever will ease their physical pain and mental anxiety. Today society wants to short-circuit the Lord’s Passion by euthanasia and assisted dying. This damaging ideology of physician/nurse assisted dying does two things. First, it prevents us from developing compassion for the dying by eliminating that period in which the greatest compassion, insight and care is required. Second, it deprives the world of graces won by the suffering Body of Christ. We must strive to ensure that those who are dying are accorded a high dignity and importance and prevent it being eliminated by euthanasia and so-called assisted dying. As health care professionals we are called and dedicated to caring, not killing. The Hippocratic Oath may no longer be taken (“I will use treatment to help the sick according to my ability and judgment, but never with a view to injury and wrong-doing. Neither will I administer a poison to anybody when asked to do so, nor will I suggest such a course … Into whatsoever houses I enter, I will enter to help the sick, and I will abstain from all intentional wrong-doing and harm …”) and Nightingale’s maxim of “First do no harm” may no longer be commonly quoted, but if we take ourselves seriously as healthcare workers, surely we have an obligation to avoid taking part in “assisted suicides” or engaging in euthanasia by commission or omission. If our philosophical system does not keep us from such actions, the Divine Law certainly does: “Thou shalt not kill”.

We ought never to underestimate the privileged position we have taken on by providing healthcare to those who suffer

Truly, those of us who care for the sick have a very privileged position: we are called to encompass the compassion of Veronica, who wiped the face of the Lord; called to imitate Simon of Cyrene, who helped Our Lord to carry the Cross, and called to have the compassion of the Holy Mother who stood by her Son to give strength and courage. We ought never to underestimate the privileged position we have taken on by providing health care to those who suffer.

Fr Dickson is a priest of the diocese of Hexham and

Newcastle, and before training for the priesthood trained and worked as a

nurse.

Fr Dickson is a priest of the diocese of Hexham and

Newcastle, and before training for the priesthood trained and worked as a

nurse.

(This article was written for us shortly after he made the difficult

decision to retire from active ministry last year. This decision was made

due to his poor health having severe COPD. At the time of writing

(December 2017) he has been in hospital for several weeks with an

infective exacerbation of COPD. The editor asks for prayers for his

recovery. He blogs at:

catholiccollarandtie.blogspot.co.uk).